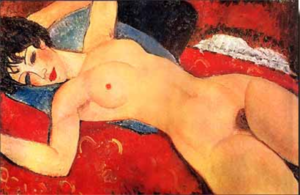

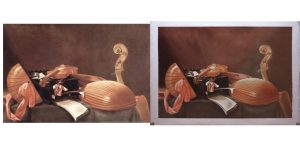

Art reproduction is a popular service in today’s art industry. It allows people to enjoy the beauty of original artwork without breaking the bank. Outpost-Art.org is one company that stands out from the rest when it comes to quality reproduction services, cost and shipping, positive reviews, and customer satisfaction.

Outpost Art

Outpost Art is a company that specializes in museum-quality art reproductions. They are dedicated to providing their customers with exceptional service and quality products.

Quality Reproduction Services

One of the main reasons why Outpost Art stands out as the best art reproduction company is because of their commitment to quality. They use only best artists to produce accurate and detailed reproductions of famous artworks. Their team of experienced artists carefully examines each piece for accuracy, color matching, and overall quality before it is shipped out to customers.

Cost and Shipping

Another reason why customers love Outpost Art is because of their affordable prices and fast shipping options. Customers can choose from a variety of sizes and finishes for each reproduction, making it easy to find something that fits their budget. Plus, all orders are shipped using reliable carriers like UPS or FedEx, so customers can be sure they will receive their order in a timely manner.

Positive Reviews

The proof is in the pudding when it comes to customer satisfaction with Outpost Art. The company has received countless positive reviews from satisfied customers who rave about the quality of their reproductions, fast shipping times, and excellent customer service.

Final Thoughts

Outpost Art truly stands out as the best art reproduction company thanks to their commitment to quality, affordable prices, fast shipping, and exceptional customer service. Whether you’re an art enthusiast looking for a beautiful reproduction of your favorite painting or an interior designer searching for the perfect artwork for your client’s home, Outpost Art has something for everyone.

Conclusion

If you’re looking for museum-quality art reproductions, look no further than Outpost Art. With their commitment to quality and customer satisfaction, it’s easy to see why they stand out as the best in the industry.

FAQs

- What types of reproductions does Outpost Art offer?

Outpost Art offers museum quality oil painting reproduction of any artwork. - How long does it take to receive my order?

Shipping times vary depending on your location and shipping method selected. However, most orders are delivered within 15 business days. - What is Outpost Art’s return policy?

If you are not satisfied with your order for any reason, Outpost Art offers a hassle-free return policy within 30 days of receiving your order.